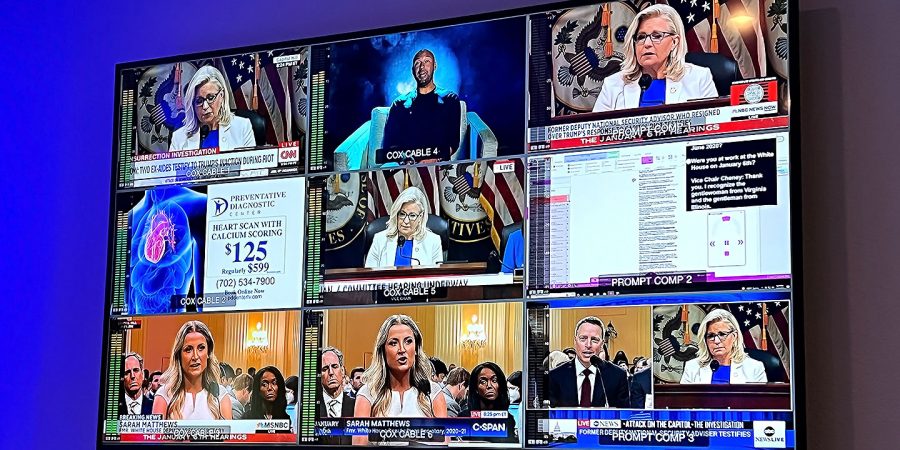

The January 6th Committee Hearings on the January 6th Attack on the US Capitol were historic from both an American history perspective as well as for the broadcasting industry. Over the course of 10 hearings, 130 million people experienced an expertly produced and highly scrutinized event.

As the broadcast director, I was thoroughly impressed by how everyone involved, from Chairman Bennie Thompson to the investigators to the administration and production teams, worked tirelessly to achieve a goal. That goal was to be truthful and transparent in telling a story about a critical event in our country’s history.

The pressure we all experienced was unmeasurable. The team felt a duty to do the job well and get it right. There were no other options.

Broadcast Management Group has had the privilege of working on many large and complex events all over the country in news, sports, and entertainment. This blog is about how Broadcast Management Group embarked on the biggest challenge in our nearly 20-year history. How did we get it done technically despite unimaginable challenges? This blog is for television production enthusiasts.

How did this project come about for BMG?

The January 6th Committee sought to produce public hearings about the January 6th attack on the US Capitol in a way that would resonate with the American people. The Committee contracted Former ABC News CEO James Goldston to executive produce the hearings for broadcast. James then needed to build his team. He needed live broadcast producers, a broadcast director, and someone to develop the technology plan to support the hearings. He also needed to build a team he could trust that could keep extremely sensitive information confidential. James reached out to some of his ABC News colleagues, who recommended me and my team at Broadcast Management Group.

After an e-mail introduction, I had a brief call with James, and from that call, we agreed that it would be good to talk in person. Although no one fully knew how this would develop, my gut told me I should bring my colleague Driss Sekkat to the meeting. I believed Driss, as an expert live broadcast producer, would be a critical part of the success of this project. Driss and I have worked on many large projects over the years, and I knew I would want him on our team. This project would become the most consequential project of our careers. After the meeting, James felt comfortable that BMG, Driss, and I were what he needed. Driss became the Senior Live Producer, and I was the Broadcast Director. Perhaps more importantly, I was also responsible for developing and overseeing the technology solution and broadcast production team. During the next ten months, we would embark on a journey together that we could have never imagined and will never forget.

What was next?

Before we knew it, we were on Capitol Hill getting on-boarded with our security credentials. We had a kick-off meeting for the initial producing team led by Communications Director for the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol, Tim Mulvey. Tim laid out the gravity of what we were about to embark on and the need for confidentiality. After that, I started to fully dive in to figure out what it would take to produce an undetermined number of hearings technologically and creatively on broadcast dates that would often only be known days before each.

It was surreal how fast everything was moving. I first assessed the technical resources of the House production facilities to see if we could leverage internal resources. The House system is designed to document a hearing for historical proposes and not to produce a major live broadcast. The house has PTZ cameras in all hearing rooms, a basic switcher, no graphics system, and no playback system. Their systems and staff are ideal for the day-to-day House needs but were not suited for something of this complexity. Bringing in a production truck was not an option for logistical reasons, and in hindsight, with the hearings spanning over ten unpredictable months, it wouldn’t have been cost-effective. At this time, we did not fully realize how complex the production workflow would be. It was an ever-evolving situation, and we had to be ready for anything at any time.

I had complete confidence that BMG’s proprietary REMI workflow of centralized technology and decentralized production staffing would be a perfect fit for our needs. This would allow us to scale staff and equipment resources as needed. Once we connected the Cannon House Office Building to our Broadcast Operations Center in Las Vegas, we could turn up and turn down production systems and production teams as needed. We were provided with a large, unmarked conference room surrounded by congressional offices above the hearing room. BMG’s engineering team built our video village in this conference room. Knowing the location of this room was on a need-to-know basis. That would be our home away from home for the duration of the hearings. The cooperation of the IT and U.S. House of Representatives production teams was essential to the success. We were all working well together.

Before I knew it, I was coming in and out of the Cannon House Office Building at all hours of the night and on weekends. It was completely unpredictable. Some days started at 2 am, and others meant leaving well after midnight.

We set up the video village much like a traditional network control room. It had a front bench for me, the Broadcast Director, and Driss, the Senior Live Producer. It had all the monitors we needed, including multi-views from the large control room back in Las Vegas, a playback canvas, a graphics canvas, a teleprompter monitor, RTS KP panels, and rundown system monitoring. The second bench had our Associate Producer for Graphics and Associate Producer for Video, along with all the necessary comms and monitoring. The third bench often had additional tape producers and investigators. Sitting alongside the front bench was James Goldston, the executive producer. We also had a Multiview of four of the major networks so we could see how they were using our content in real-time. Also in the room was our on-site Engineer in Charge. Depending upon the hearing, we would have 8-16 people in the room. It would get very intense the day of shows leading up to the broadcast, but just before we would go live, James would put his arms around Driss and me and say, “Have a good show.” He knew that, at that point, it was up to us to deliver his vision. We felt the weight of that responsibility and did not want to let him or anyone else on the team down.

What many people had yet to learn was that the team in the House conference room was just the tip of the iceberg, from a broadcast perspective, of what it was actually taking to get the hearings on the air. The technical center was 2,500 miles away in Las Vegas. And those who weren’t in the Washington DC control room or in the Broadcast Operations Center were scattered throughout the country from Chicago to New York City to Las Vegas.

The off-site crew at our Broadcast Operations Center included our Technical Director, Playback, Prompting, Engineer in Charge, and with some of the hearings, our A1. In some hearings, we used our A1 at our New York facility, and Xpression Graphics was primarily done out of Chicago. For the final hearing, our primary Teleprompter operator, Will Mason, and our leading playback operator, Drew Hallett, were with us, operating from the Cannon House Office Building above the hearing room.

The technology used

Control Room Equipment

- Ross Acuity 3 ME switcher

- Ross Tria 4-channel playback system

- Ross 4-channel Xpression

- Ross Inception Rundown system

- CueScrip Teleprompting system

- Yamaha CL5 Audio Console

- RTS Oden Comms system

- BMG’s proprietary remote Multiview system

Transmissions

5 LU 610 and 2 LU 4,000, between the Washington DC and the US Capitol, redundant gig internet circuits, and bonded cellular, we had two fiber lines to the media. One feed was equipment in a completely different building for redundancy. (Rayburn building)

In addition to the equipment in the video village and back at the Broadcast Operations Center, we had our LiveU encoders and decoders in the actual hearing room connected to the House system. BMG provided a program feed to the large projection screen in the hearing room, a downstage monitor, and a feed to the networks, which they all received via fiber. BMG also provided a teleprompter to two of the downstage monitors.

How we provided the media and the public transparency

It was important that each network could cut and control its broadcast. The pool network for this event was C-Span. They provided 7 cameras on site. Each camera was a home run to each pool network member, along with what was referred to as the Multimedia Feed, which was the audio, video, and graphics our team produced. Each pool network REMIed into its control rooms, primarily in Manhattan, so they could independently cut their programs.

Before each hearing, there would be an editorial meeting with the pool member networks and the January 6th Committee communications team to distribute sharable information. We would also have a separate technical meeting between me and the pool networks to discuss the pending hearing’s technical logistics and scheduling. The networks appreciated that I was one of their own. They felt secure knowing I understood their needs and would provide the information and tools to do the best job. I did that while maintaining the confidentiality of the Committee.

Leading up to Each Hearing

We did not have a hearing schedule. Several factors would go into when the hearings would take place and whether they would be in the early afternoon or prime time. I would typically get a call from James a few days before the hearing to let me know it’s time to get the team together. We would typically have a table read first without the production crew. Then a full rehearsal would occur with the Members that afternoon or the next day. There would then be one more rehearsal on the day of the hearing in the morning, generally at 8 am. After each rehearsal, almost everything would change, the script and graphic elements would need to be redone, and video elements would need to be re-edited. If we had a rehearsal at 7 pm, we would need a crew call at 1 pm to load the scripts and all the graphic and video elements. We would finish the rehearsal around 10 or 11 pm, depending upon the length of the hearing. Then the producing team would work all night making all the changes determined from the hearing rehearsal. If we had a rehearsal at 8 am, our production crew call time would be 3 or 4 am. The production team had many very long days with short turnarounds. Frequently the producers would go two days with little or no sleep.

The process from post to production

The editors worked on Adobe Premiere. Once the elements were approved, they would upload them to Box, the Congressional team’s secure cloud storage system. BMG would import the files from Box into our servers and then to our Xpression graphics system and Tria video playback system. This was not the fastest process, but it was the environment we had to adapt to. Scripts were another story. Many people were involved in developing each Committee Member’s script. That meant the investigators, producers, members of staff, and Congressional Members had a hand in script creation. Once it was all approved, it would be given to the production team for the producers to load into Inception. Once loaded into Inception, our prompter operator would review and format it. Once the script was in Inception, I would go through the rundown, assign the naming convention for video and graphic elements, and add the production cues to the script. On every hearing, graphics, video, and script changes would go right up to the rehearsal start times and the beginning of a broadcast. We had four video channels and four graphic channels. Sometimes, I only saw the final graphic or video when I called for it in the live broadcast to run on air.

Everyone felt the full magnitude that everything we did had to be perfect, with no mistakes, regardless of the cards we were often dealt. Running the wrong graphic or video could have substantial legal and political consequences. We had an AP for Graphics that would double-check each element before I would take it to air, and the same with the AP for Video. I would tell the graphic operator to load A in Ch 1, B in Ch 2, C in Ch 3, and D in Ch 4, and the graphic producer would verify each matched the script and was correct. The exact process would go for the four channels of video. The speed at which this would all happen was incredible. As a director, you must have 100% confidence in every team member. I was fortunate to have such a fantastic team. We produced ten flawless hearings. James would sometimes ask how I stayed so calm, and it was because I was 100% confident in every person I had working on our team.

The Day of Each Hearing:

On the day of the hearing, we would have a final rehearsal in the morning with the Members that would run directly into the limited time scheduled for the fac out of the audio, video, and comms with the broadcast networks. We would have to break for 45 mins for the security sweep. If our rehearsals ran late, that would put a lot of pressure on the networks because it would shorten their test time. 30 mins before each hearing, I would have a call with the network producers and directors to review what was expected at the hearing. That included:

- Projected hearing length

- Start time (usually 1 min after the hour)

- Recess length

- Number of witnesses participating (if any)

- Number of video and graphic elements

- Content warranting a warning

I would then take any questions from the networks. This was very important because they did not have a copy of the rundown or script.

During the live hearing

Many people have commented on how choreographed it all was on television. This is how that happened:

On my RTS panel, I had keys for the BMG team that included production, graphics, video, audio, prompter, and EIC, but I also had a pool and DIRL (Director Listen) channel. On the pool channel, I was connected to each pool member’s control room (directors/producers), and they could hear me call the show. If they had a question like how long back or what exhibit the video is for, they could ask, and I would respond.

The DIRL (Director Listen) channel was for non-pool member media; they could listen to my calling the show but could not talk back. Our show was called Multimedia Feed. All the audio and video content played out in the hearing room. Whenever we were not playing an audio or video package, we would go back to the January 6th graphic.

Calling the show for the BMG team was like any other live broadcast, standby to roll red, roll red, track red, take the red. The networks would hear this, but before each call, I would add coming up is a 1 min package, Exhibit 23B, so they would know what the graphic was for the video I was referring to. I would also give them a heads-up during a package about what would be coming up next since they did not have access to our run of the show. Seeing where the member was in the teleprompter copy, I could give the networks a heads-up before rolling a video or graphic. I would count them out of an element, returning to the January 6th graphic. That way, they could decide if they wanted to transition from the multimedia feed toward the end to a wide shot of the hearing room.

Each hearing generally started 1 min after the hour. I had Hannah Muldavin, Deputy Communications Director for the January 6th Select Committee, backstage with the members on comms; I would check with her to ensure the Members were all ready. If they were ready, I would give the count to the door opening, where the members would enter. The networks would let their anchors know we were starting and have cameras on the door to catch the members coming out. Our recess was generally 10 minutes, but once we went into recess, I worked with the pool members, and we agreed on the exact time. This would accommodate commercial breaks and anchor lead-ins. Again, to start after recess, I would check with Hannah backstage to confirm the Members were ready, and if so, I would count back to the Members entering. If there were any issues with a Member and we would need to delay a minute or so, I would communicate that with the networks.

In Summary

There was a lot of pressure leading up to the first hearing, unlike anything I had ever experienced. Seeing the reaction of the public and the media after the first hearing was astounding for all of us. That hearing reached more than 20 million viewers. This was the first time anything like this had been done for a congressional hearing. The pressure only increased over time as we wanted to build on the success. As a result, the expectations only increased. I had confidence that we had the right team and had developed a great technical solution, but this is live television, and anything can happen. I truly appreciated the opportunity presented and look forward to how we will conquer an even bigger challenge in the future. I know we are ready!

BMG Production Team

Todd Mason

Driss Sekkat

Justin O’Neil

Brian Sasser

Ron Paul

Nit Maokhamphiou

John Allen

Gianlucca Trombetta

Drew Hallett

Nit Maokhamphiou

Will Mason

Ryan Eicher

Claire Pilarski

Colin Tuttle

Sean Wybourn

Mark Ott

Gerard Cana

Jordan Wiessen

Mike Dubrin

Andrew Ryback

Leslie Silva

Leave a Reply